Student Stories

Redlich Studies Genetics and Sleep In Dream Research Project

Ruby Redlich’s interest in genetics and sleeping patterns first awakened when she took an introductory computational biology class with Andreas Pfenning, assistant professor of computational biology.

“He had talked about some projects his lab was working on, and it seemed really interesting,” said Redlich, a senior in biological sciences with a secondary major in computational biology. “I liked the balance in his lab between biology and computer science.”

Redlich joined the Pfenning lab in fall 2021. Under the mentorship of Pfenning and Amanda Kowalczyk, a Neuroscience Institute postdoctoral fellow, she started developing her own research into the evolution of different sleeping patterns and how they are related to genetic markers.

I feel like it’s impossible to overstate how incredible Ruby is at doing research — it’s genuinely been a joy to work with her and watch her quickly progress and discover new things.

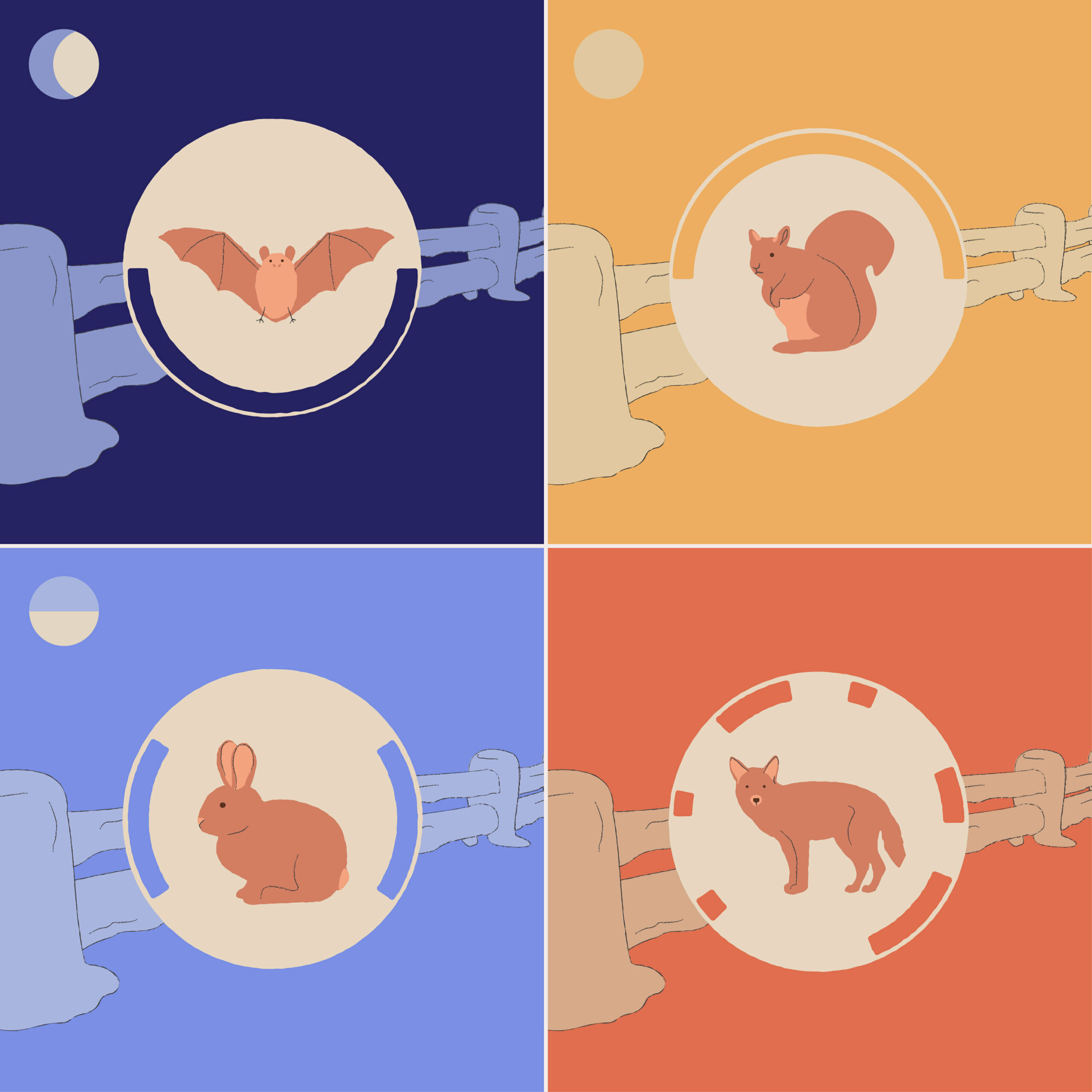

Animals follow four major kinds of sleeping patterns: (from bottom left) nocturnal, diurnal, crepuscular and cathemeral.

SLEEP CYCLES

Animals follow four major kinds of sleeping patterns: nocturnal, diurnal, crepuscular and cathemeral. Nocturnal animals such as bats are awake at night, diurnal mammals such as squirrels are awake during the day, crepuscular animals such as rabbits are active at dawn and at dusk, and cathemeral mammals such as coyotes have no consistent sleep schedule. Animals in the same order or family can have different sleep patterns.

In the past, researchers have found that sleep patterns are genetic. Redlich wanted to use computational tools to see which genetic markers most determine sleep patterns and how those markers present across mammals.

“I feel like it’s impossible to overstate how incredible Ruby is at doing research — it’s genuinely been a joy to work with her and watch her quickly progress and discover new things,” Kowalczyk said. “She’s never been afraid to jump right in and take ownership of her project, dig around in the literature to learn everything she can, and become a true expert in her research topic. I think that kind of initiative is what makes her really exceptional.”

In her preliminary results, Redlich found that a specific gene implicated in sleep regulation, FAM217A, has evolved differently in nocturnal mammals and causes different behavior compared to cathemeral and diurnal mammals.

“What I find really exciting is that we’re able to use computational tools to predict ancestral history,” Redlich said. “We predict how the current day species may have evolved from their most recent common ancestor, so even though we don’t know that, we’re able to predict that using these computational tools. Then, we actually factor that information into our analysis.”

Redlich’s research was funded through a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) grant by the Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholar Development, which provides $3,500 to CMU undergraduates conducting full time summer research.

Pfenning said that the tools she is creating could be of significant use across projects related to links between genomes and behavior.

“What we’re interested at the higher level is basically how differences in the genome relate to differences in complex behavior,” Pfenning said. “Within the human population, that might be a genetic difference that might lead to Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease or even differences in sleeping behavior. But across species, that means that there’s a genetic difference across mammals that might lead to differences in the sleeping behaviors of those mammals.”

A CMU alumnus who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in computer science in 2006, Pfenning supports undergraduate research in part because it’s where he began lab work.

Ruby Redlich competes as part of the CMU varsity swim team.

“I’ve been swimming since I was little, so I definitely think it’s the same commitment as lab work,” Redlich said. “It’s trying to work at something even if it’s difficult in the moment because you know it will be gratifying.”

Redlich said she plans to continue her research and hopes to further develop her skills. If given the chance, she is aiming to continue in the Pfenning lab as a doctoral candidate in the future.

“Ruby’s just incredibly talented,” Pfenning said. “She has this knack for understanding and making progress on computational theory.”

■ Kirsten Heuring