In Memoriam

Julia and Johannes Weertman

The Weertmans were an academic power couple and materials science experts whose research spanned decades and garnered them multitudes of awards. Julia and Johannes “Hans” spent their professional careers at Northwestern University, each holding the title of Walter P. Murphy Professor Emerita/Emeritus of Materials Science and Engineering, respectively.

Julia passed away on July 31, 2018, at age 92. She was the first woman admitted to the College of Science and Engineering at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon) where she earned her bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in physics. She joined Northwestern University in 1972 as an assistant professor. In 1987, she became the first woman in the country to be appointed chair of an engineering department. During her five-year tenure, the number of materials science undergraduate students more than doubled, and she recruited two new female faculty members to join the department.

In 2014, she received the John Fritz Medal — the highest award in the engineering profession — from the American Association of Engineering Societies, in recognition of her exceptional contributions to the understanding of failure in materials and for inspiring generations of young women to pursue careers in the science and engineering disciplines.

During decades of research and scholarship, Julia advanced understanding of the basic deformation processes and failure mechanisms in a wide class of materials, from nanocrystalline metals to high-temperature structural alloys. Hans heavily contributed to the study of the mechanical properties of materials, particularly to the fatigue and fracture of metals, the high-temperature creep of crystalline solids and dislocation theory. Together, they co-authored the 1964 textbook Elementary Dislocation Theory, which stands as the first book written specifically for undergraduate students on dislocation theory.

In honor of the couple’s impactful contributions to materials science and to Northwestern, the university established the Johannes and Julia Randall Weertman Graduate Fellowship in 2014. And in 2017, The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society (TMS) renamed its TMS Educator Award to the TMS Julia and Johannes Weertman Educator Award, celebrating their commitment to education in materials science and engineering.

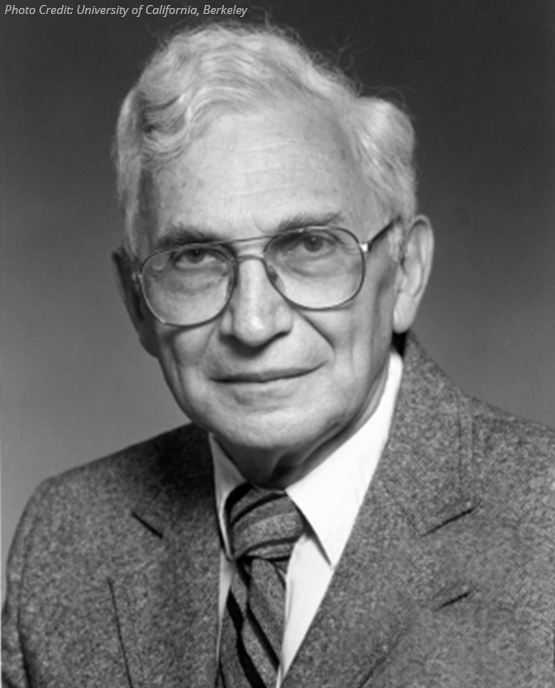

Frederick Reif

Emeritus Professor of Physics and Psychology Fred Reif passed away on Aug. 11, 2019, at age 92.

Reif emigrated from France to New York in September 1941. He and his family were Jewish refugees, who escaped from Austria to France with the rise of the Nazi regime. At age 18, Reif was drafted into the U.S. Army and was sent to Yale University to learn Japanese. After serving in World War II, Reif earned his bachelor’s degree from Columbia University in 1948 followed by a Ph.D. in physics from Harvard University.

A member of the Carnegie Mellon faculty for 11 years, Reif previously taught at the University of California, Berkeley for 29 years and the University of Chicago for eight years. He held the status of professor emeritus at both UC Berkeley and Carnegie Mellon.

Reif had a prolific scientific career, studying a wide range of topics from superfluids to cognition and education. He wrote several physics textbooks that remain standard texts in the field today. He also was among the pioneers in the development of physics education research in the 1960s. He co-founded the first formal interdisciplinary Ph.D. program in science and mathematics education at UC Berkeley in 1969. At Carnegie Mellon, he introduced interactive teaching methods like concept tests in lectures to gauge student comprehension (early precursors to today’s “clickers”).

Paul David (Dave) Luckey

Dave Luckey was an experimental high-energy physicist who specialized in the use of crystals for electromagnetic calorimeters. He passed away on April 1, 2019, at age 90.

A Pittsburgh native, Luckey received his bachelor’s degree in physics from Carnegie Institute of Technology. In 1952 he earned his Ph.D. in physics and astronomy from Cornell University and continued on as a postdoctoral fellow at the university until 1958.

Luckey was an innovative scientist, relentless in his research pursuits. In 1962 he invented the light pipe for large-area scintillators, a detector development that benefits particle physics to this day.

Throughout his 40-year career, Luckey worked as a research scientist and later a senior research scientist at MIT and collaborated with scientists at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) and Fermilab.

After retiring in 1998, Luckey became an emeritus member of the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) collaboration at CERN. During this time, he worked mainly on the CMS electromagnetic calorimeter and coauthored several publications on hadron damage to inorganic scintillators. His theory that hadron damage to lead tungstate crystals was due to Rayleigh scattering off fission tracks was a decisive input in the decision to replace the CMS electromagnetic calorimeter endcaps.

Winston Ko

Winston Ko, one of the first United States researchers to join the CMS experiment, passed away on July 26, 2019, at age 76.

At 18 years old, Ko immigrated to the U.S. from China to pursue his education. He earned his bachelor’s degree at the Carnegie Institute of Technology and a master’s and doctorate in physics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Ko dedicated his 41-year-career to the University of California, Davis. He arrived in 1970 as a postdoctoral scholar before officially joining the Department of Physics faculty in 1972. He retired from the university in 2013, having served as department chair for five years and later as dean of the Division of Mathematical and Physical Sciences for 10 years.

Ko had a distinguished career as an experimental particle physicist and performed experiments in high-energy physics laboratories around the world: he surveyed inclusive reactions during the pioneer days of Fermilab; he measured the structure of the photon in SLAC and DESY; and he studied electroweak symmetry breaking in Japan’s KEK accelerator laboratory.

In addition to research, Ko was dedicated to improving science education. Influenced by his experience at Carnegie Tech, Ko’s educational philosophy emphasized foundational learning and hands-on problem-solving skills. At UC Davis, he facilitated and supported an “inquiry-based” introductory physics course and pioneered one of the nation’s first calculus for biology and medicine programs.

■ Emily Payne