Snyder, who helped found a science demonstration outreach program during graduate school, figured he would toss his hat into the ring.

“I thought I’ll go and do that for a couple years. How often do you get to build a new science center? And then I’ll come back to academia,” Snyder recalls. “And I just never came back.”

He fell in love with the work, and that was that.

Within five years, Snyder saw Kansas City’s Union Station, the second largest train station in the country, transform from an abandoned and dilapidated property into a series of museums and other public attractions, including Science City.

Working with a small team, Snyder got to try his hand at a little bit of everything from construction and exhibit design to branding, marketing and fundraising. After a successful launch, Snyder saw new doors opening. He received an offer from Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute, one of the oldest science centers in the country, to serve as vice president of exhibit and program development.

Snyder and his team reimagined 80,000 square feet of new exhibitions and programs exhibits. “Science centers are a connection between the scientific enterprise and the public. You’ve got to find the space where they’ll come together,” Snyder said. He notes it takes a mix of creativity, research and marketing to bring to life exhibits that will thrill visitors. At Franklin Institute, they launched new exhibits on augmented reality, climate change and started a popular Science Festival.

But for Snyder, often the best part is making interactive exhibits that can immerse people into a new world or a place in time. One such experience is the Franklin Institute Air Show.

The exhibit showcases festival booths set up to celebrate the history of aviation, along with a flight simulator, pilot training, the famous Wright Model B Flyer and a T-33 jet trainer, all set up on a tarmac under a vaulted sky ceiling. “It really makes you feel like you’re someplace completely different,” said Snyder.

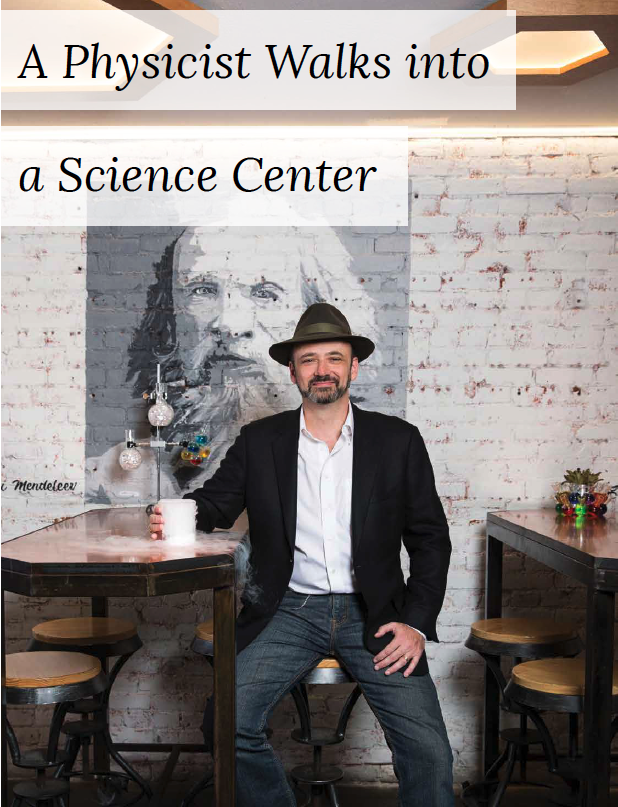

After 12 years in Philadelphia, Snyder received another offer. He was recruited to be the president and CEO of the Fleet Science Center in San Diego, California.

Since 2013, the Fleet has flourished in the local community under his leadership. The Fleet has grown from a museum in Balboa Park to a county wide organization launching 52 Weeks of Science, where each week researchers, engineers and scientists bring educational science center experiences to local neighborhoods, and the national movement Two Scientists Walk into a Bar.

“Science is beautiful that way.”

“We have people actually bar hop to talk to scientists at different bars across the city. And we have well over 300 scientists who sign up who want to do this now. It’s kind of competitive if they get a slot,” said Snyder.

The Fleet has also helped other cities implement the same kinds of programs, Pittsburgh included. They provide free marketing materials and licensing of the name and let cities run with it. (The program has been discontinued during COVID-19.)

In each of his roles, Snyder says his favorite part has been helping other people do their best work. “If there’s an accomplishment, it’s being able to create a space where people can excel, be creative and really bring what we do to life.”

That’s what makes his work exciting. He’s loved working with not just scientists but engineers, artists, educators and community leaders to share the experience of science with the public. Snyder believes the mission of science and science centers is vital and helping others to discover and find inspiration in science is incredibly powerful.

“That moment where a child suddenly sees a new view of their world or a new possibility for themselves, it’s something I believe can make the world a better place.

“Science is beautiful that way,” he said.

The passion that Snyder has now is reminiscent of what he learned at CMU. “This idea of speaking with passion about what you do is something I still try to channel to this day,” he said.

He says that his education also prepared him for something that he couldn’t even conceive of being prepared for. “I certainly had no idea this job existed when I entered college,” Synder said.

But now that he does know, he can’t picture himself anywhere else.

■ Emily Payne