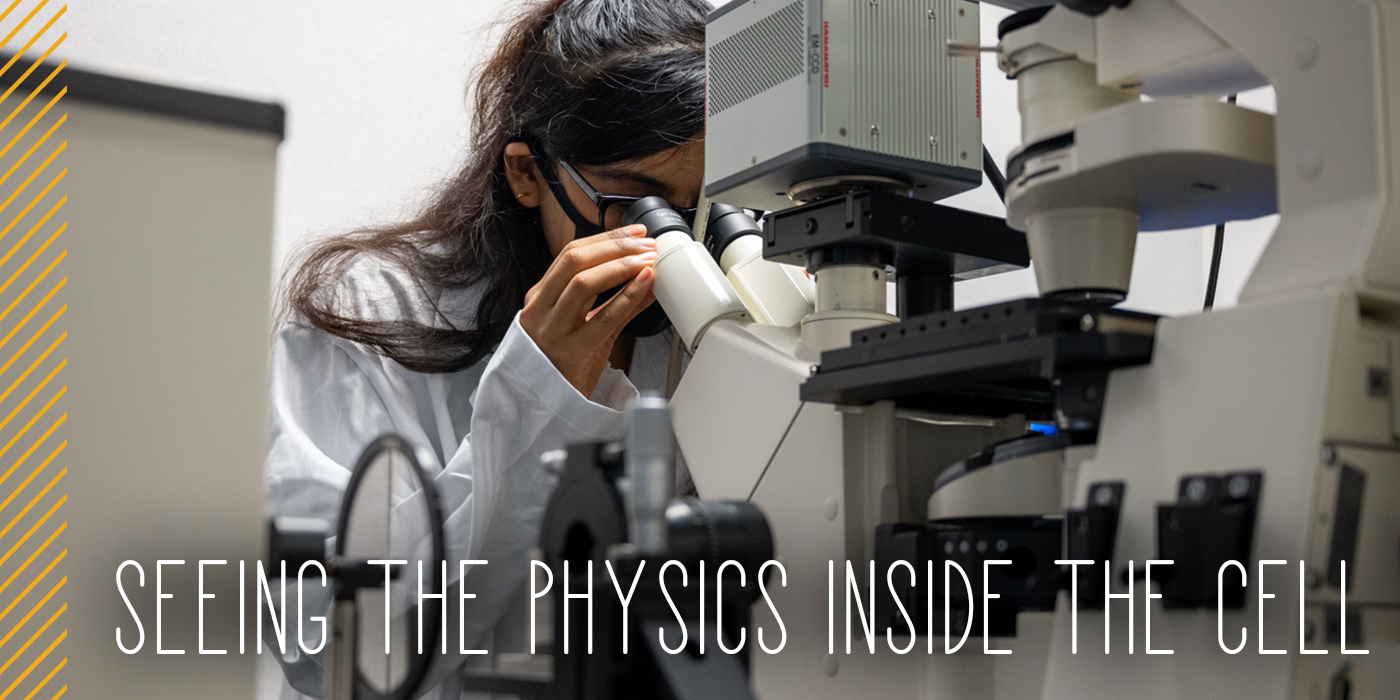

Within every living cell, a vast array of complex processes supports the functions that sustain life. Understanding the physics behind those biological interactions is the mission of Associate Professor Ulrike Endesfelder, who joined the faculty of the Department of Physics this year.

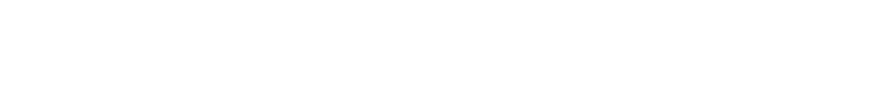

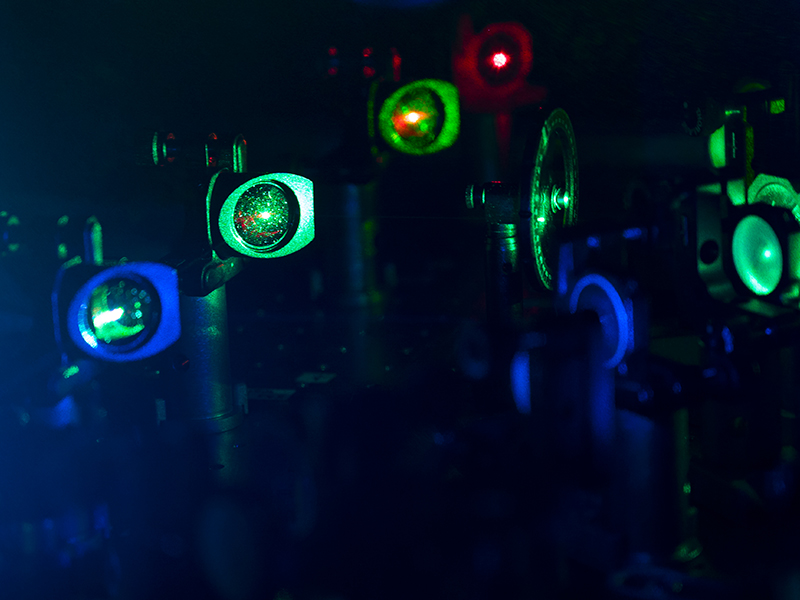

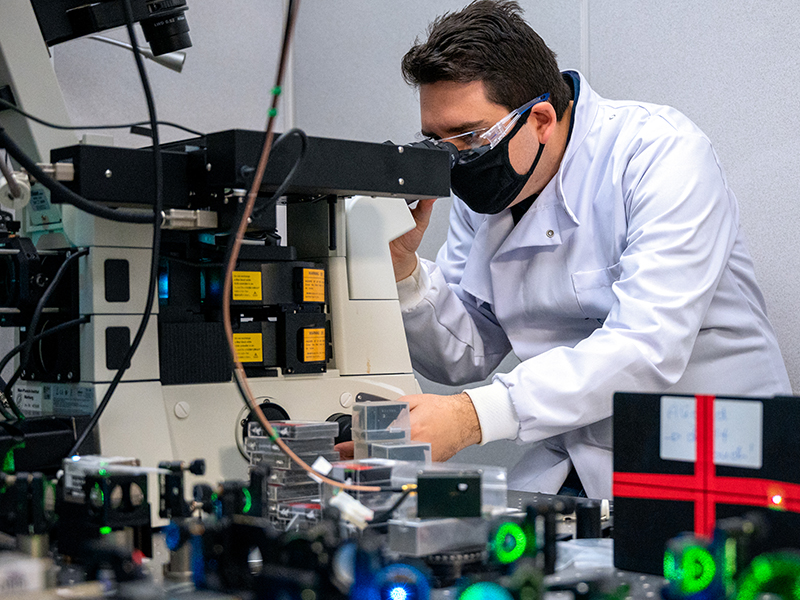

“We do what we call single-molecule biophysics,” Endesfelder said of her lab’s research, which works with a technique called Single Molecule Localization Microscopy to image the tiny structures within fluorescent molecules.

“The beauty of the technique we are using is we can localize single molecules in living cells,” Endesfelder said. This represents a sharp break from previous biochemistry work on the structures and mechanisms of cells that required purifying the cellular components of interest in test tubes to study them.

While it’s much more complicated and data intensive to observe live cellular structures and mechanisms, Endesfelder noted, the benefits are clear.

“It gives us the strong advantage that we really can observe the molecules in their native environment and see what they really naturally do,” she said.

Ultimately, Endesfelder hopes her research can contribute to a better understanding of diseases by allowing researchers to model how they affect cellular processes over time.

Endesfelder was previously based at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Marburg, Germany, where she led a team of physicists, biologists, chemists and computer scientists. The interdisciplinary nature of her research was a major motivating factor in choosing to relocate to Carnegie Mellon University.

“What convinced us was this very collaborative feeling when I interviewed,” Endesfelder said. “Even if it’s not their topic, everyone is excited and interested in your work.”

Before she could get to work on her research at Carnegie Mellon, however, Endesfelder and her research group had to make it to Pittsburgh, and that proved to be more challenging than they anticipated.

In preparation for an April start on campus, Endesfelder and her team resigned their positions and packed their entire lab into containers to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean on March 9. Two days later, as the COVID-19 pandemic began to surge, the United States banned all migration from European Union countries.

“It gives us the strong advantage that we really can observe the molecules in their native environment and see what they really naturally do.”

Endesfelder and her researchers were now left jobless, homeless and without any of their scientific equipment. Luckily, they were able to be temporarily reemployed by the Max Planck Institute and move in with their families. And when it came to research, Endesfelder pointed out that her team was more prepared than most labs for the disruptions brought on the novel coronavirus.

“We were basically prepared for a lockdown because we prepared our own group lockdown due to the move,” Endesfelder said. “We were prepared for two to four months of computer work.”

Gradually, Endesfelder and her lab were able to travel to Pittsburgh by stopping in Serbia, outside the European Union, for two weeks and then flying to the United States. Since November, the group’s wet lab and optical microscopy lab have been set up and are ready to go. “Finally, we are back to hands-on experimental research,” Endesfelder said.

While dealing with the difficulties in her own life and work brought on by COVID-19, Endesfelder also took time this summer to help shine a spotlight on the problems the pandemic was causing for other scientists.

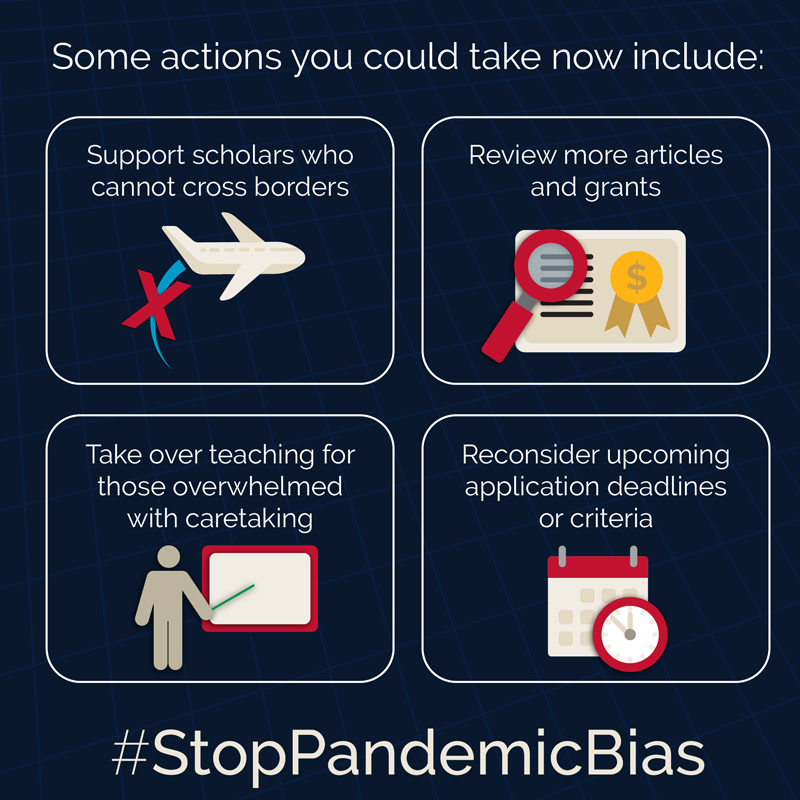

After lockdowns forced many labs around the world to shut down, Endesfelder saw many of her colleagues struggle with being unable to complete experiments, balancing childcare and work, being unable to travel to take on new positions and even dealing with sickness themselves. These problems are especially common and difficult for younger scientists who are finishing their Ph.D. work or seeking postdoctoral positions, which are rare under current hiring freezes.

In collaboration with several scientists in Germany, Endesfelder wrote a letter in the journal Nature urging the scientific community to recognize and challenge these issues. While she has been happy to see many scientists sharing their stories and suggestions using the Twitter hashtag #StopPandemicBias, Endesfelder said there is still a lot of work to do to avoid lasting damage to the careers of students and researchers.

“The problems are not solved and being unaffected by COVID-19 is still an ongoing privilege,” Endesfelder said, stressing that nobody should be forced out of academia by this pandemic bias. She noted that everyone can contribute by becoming aware and helping those around them.

“#StopPandemicBias is a community effort that values our diversity, and as such benefits all,” Endesfelder said.

■ Ben Panko

The Department of Physics has been selected to join the American Physical Society’s Inclusion, Diversity and Equity Alliance (APS-IDEA). The effort to join the alliance was led by Professor of Physics Rachel Mandelbaum.

APS-IDEA aims to create a collaborative network working to improve equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) across the physics community. Supported by the APS Innovation Fund, representatives from tens of physics departments, laboratories and research collaborations were selected to participate in APS-IDEA to help their institutions identify effective, research-based practices to improve their EDI efforts and develop an actionable and strategic 10-year plan for EDI.

Physics has long had problems in diversity, noted the APS. Women, people of color and people with disabilities are vastly underrepresented. And a lack of data prevents physics organizations from understanding the representation among the LGBT+ community and other ethnic groups such as Arab Americans, Pacific Islanders and Southeast Asians.

Members of underrepresented groups can face serious issues such as marginalization, harassment and discrimination because of their identities, further keeping them out of the field. Representation is a first important step in making sure people are not only a part of a community but welcome in that community. “People need to feel like they belong,” said Mandelbaum.

“People need to feel like they belong.”

Over the last few years, the Department of Physics has dedicated a lot of energy to improving its own culture. In May, the department formed an internal EDI committee, composed of faculty, postdocs, graduate students and undergraduates, which will be heavily involved in disseminating resources and enacting practices from APS-IDEA. The group Constructive Interference, started in 2016, supports women and minorities, providing opportunities for connection and discussion and advocating for inclusive practices. In January 2020, the department co-hosted a regional APS Conference for Undergraduate Women in Physics.

Additionally, the department made sure that female physics professors teach introductory physics courses after CMU’s Women in Science club voiced concerns at a faculty meeting that previously students weren’t taught by a female physics professor until the spring of their sophomore year.

But there are areas where the department struggles. The numbers of underrepresented minorities are low. And like many physics departments, the fraction of women decreases as you go up in seniority, said Mandelbaum. Identifying strategies to improve undergraduate and graduate representation and support people of color and women in the department will be an important goal for the committee.

“The unfortunate reality is that Rachel and so many others have run into impediments when simply trying to do physics. The good news is that she and others on the committee are motivated to help us change,” said Dodelson. “Simply put: we recognize that we need to change, and I am optimistic that we will.”

■ Emily Payne

Virtual Classes Allow Physics Professor to Invite Distinguished Guest Speakers

“I realized this was an opportunity to bring them in touch with famous people, to make the course more inspiring and to break up the monotony of the remote experience,” said Professor of Physics Scott Dodelson, who also serves as head of the Department of Physics.

Among those accepting Dodelson’s invitation to speak to his spring 2020 Quantum Mechanics class was his friend Brian Greene, a Columbia University physicist and science communicator who’s written multiple bestselling books and hosted programs on PBS. “He had some great stories about appearances on the Colbert show,” Dodelson said.

Also dropping by via Zoom was James Peebles, a Princeton University physicist who shared last year’s Nobel Prize in Physics for his research on physical cosmology. Dodelson noted that Peebles was excited to drop by because he’d felt so “cooped up” under quarantine in his home.

Dodelson also arranged for Sean Carroll, a theoretical physicist at the California Institute of Technology, to give a full lecture to his students. Carroll is an influential science communicator known for appearing on television programs on the History and Science channels and for his popular science books and newspaper articles.

Noting the very positive reception by his students, Dodelson said he plans to consider bringing in guest speakers for his future classes.

■ Ben Panko

NEW FACULTY: Gillian Ryan

Gillian Ryan joined the Department of Physics, filling the critical role of Director of Undergraduate Affairs. The position was created to emphasize the importance of teaching and advising in the department.

“We aim to provide students with access to state-of-the-art research and other benefits of a large university while maintaining the small-school community feeling that is our hallmark,” said Department Head Scott Dodelson. “The Director of Undergraduate Affairs has the responsibility of fostering this community and ensuring that each student gets the individual attention that will empower them to succeed.”

Throughout her academic career, Ryan constantly felt the pull towards teaching and interacting with students.

“For me, teaching, mentoring and advising undergraduate students are the most rewarding and fulfilling aspects of my work,” Ryan said. “[The Director of Undergraduate Affairs] position appealed to me because of the many opportunities it provides to apply my professional strengths to support a large, diverse group of physics students.”

Ryan earned her bachelor’s degree in physics from St. Francis Xavier University and her Ph.D. in physics from Dalhousie University. She comes to CMU from Kettering University in Flint, Michigan, where she had been a faculty member since 2013.