Connections

Graduate mentors guide undergraduate research

Graduate students are valued mentors to undergraduate researchers in the Department of Chemistry’s laboratories, often overseeing their day-to-day work.

“Research mentors provide a very different role than academic advisers or other faculty they are meeting through classes,” said Karen Stump, director of undergraduate studies and a teaching professor, who added that labs can be the place where undergraduates go to do homework or get personal or professional advice. “Over time, the labs become a second home to students.”

Associate Chemistry Professor Stefanie Sydlik, whose research career began as an undergraduate at Carnegie Mellon, now leads a research team that specilaizes in the design and synthesis of novel polymers and graphenic materials for use in biomedical and human health applications. The Sydlik Group currently has nine undergraduate researchers — an all-time high for her lab.

“They outnumber the graduate students. But they are a really important part of my group culture,” Sydlik said. “All of my graduate students have an undergraduate who they’ve worked with, and most have co-authored papers with them.”

Graduate students in Sydlik’s lab begin mentoring their second year. One of the first to do so was Karoline Eckhart.

Eckhart, who finished her Ph.D. in 2022 and is now a senior scientist at L’Oreal, set up a system where students train each other, a technique she learned as an undergraduate at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo.

“If you were a junior or senior in the lab, you would train the freshmen and sophomores who were coming in and get them up to speed on a project. Our adviser would help us all design experiments and support the older students teaching the younger students,” Eckhart said.

Eckhart started training two undergraduate students in her second year of graduate school. The following year she took on a third student, until she had four or five working at a time.

“There wasn’t any additional resources toward me for taking on undergraduates, but I was in a lucky position not many CMU graduate students have,” said Eckhart, whose research was supported by an NSF grant, which meant after her first year, she was relieved of teaching assistant responsibilities. “I wasn’t devoting 12 hours of my week to teach. If there could be some kind of financial support from the university, I feel like more grad students would be willing to take undergraduates.”

If there could be some kind of support, I feel like more grad students would be willing to take undergraduates.

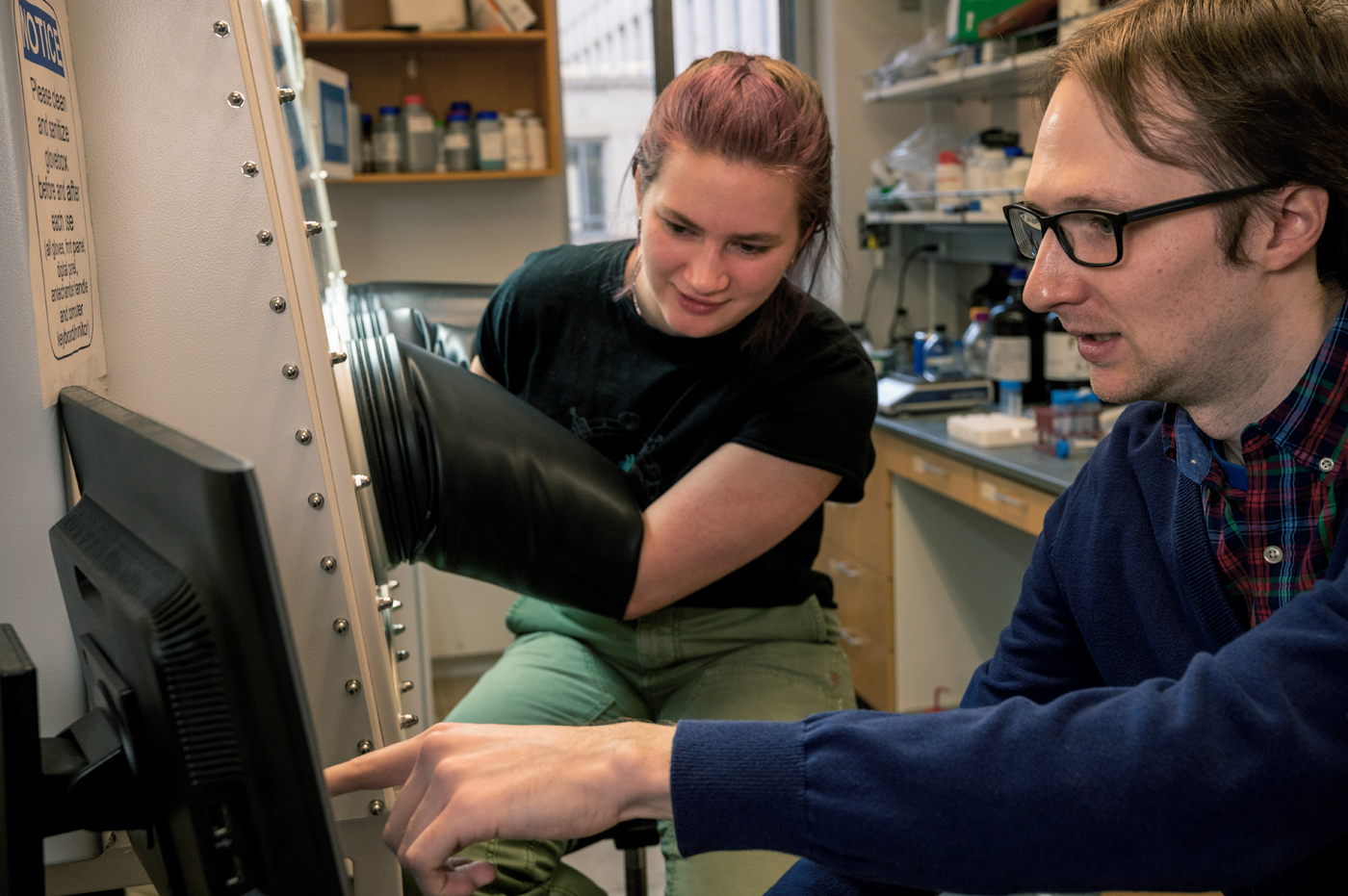

Martha Spletzer works with Jared Paris to synthesize enzymes.

Among Eckhart’s mentees is Anna Watson, who joined Sydlik’s lab at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic during her junior year. She started working with Eckhart on procedures, but by the end she was designing experiments and troubleshooting. She also served as first author on a paper.

“Having tried to mentor a student myself, I have come to understand that it takes a large amount of organization,” said Watson, who stayed in Sydlik’s lab to complete her master’s degree in 2022 and is now a doctoral candidate at the University of Toronto. “I truly admire how good of a mentor she was to be able to manage all of us and be highly productive. She was very good at ramping the responsibility I had.”

Terry Collins is the Teresa Heinz Professor in Green Chemistry and the director of the Institute for Green Science. His group currently comprises Aleksandr Ryabov, a research associate; four graduate students and four undergraduates who work on catalysts, known as TAMLs, that provide environmentally friendly methods for breaking down toxic compounds that contaminate water.

“It’s healthy in every way to have undergraduates in research, and the critical thing in how you do that lies with mentors,” Collins said. “They’re learning from us the most important problems.”

In the Collins Group, undergraduates start with simple instrumentation then progress to data analysis, more complex machinery, presenting findings at the team’s weekly meetings and writing papers. Checks and balances are in place to assure the data is within standard deviations. Frequently students will begin to conduct their own research supported by funding through Carnegie Mellon’s Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarly Development.

“We’ve had phenomenal success,” Collins said.

Parameswar Pal, a doctoral candidate in his group, had just joined Collins’ lab when Marcus Schafer, now a junior in chemistry, also joined the group.

“We learned together about the chemicals and instruments in the lab, and I helped him learn some of the techniques,” said Pal, who currently oversees two undergraduate students. “Mentoring takes a significant time when students are new. For the initial part, I provide them a project. But once they gain experience, they propose new interesting ideas.”

Jared Paris, a Ph.D. student in Associate Professor of Chemistry Yisong (Alex) Guo’s group, worked closely with senior Martha Spletzer to help her analyze enzymes containing iron ions. They hope to use this enzyme to target specific proteins that promote cell growth. Together, they have co-authored a paper with Guo on the research they conducted.

“It has been quite rewarding to mentor Martha over these past few years, particularly with how much she has grown as a scientist,” Paris said. “She has a bright future ahead of her.”

■ Heidi Opdyke