“He calls me and he tells me ‘How would you like to testify in front of Congress?'” Muzzio recalled. Months later, Muzzio found himself speaking (virtually) as a witness during a September hearing of a subcommittee of the House of Representatives’ Committee on Science, Space and Technology.

The topic of the hearing and his testimony was how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected university research, and it was unfortunately a subject that Muzzio had a lot of personal experience with.

“All of my research facilities require multiple people to be in an enclosed environment for long periods of time. My collaborators and I use the same tools and at times need to be overlapping in space, using the same gloves and viewports on instrumentation,” Muzzio told the subcommittee. “Today, none of this work can take place without extreme caution to prevent the spread of COVID-19.”

Muzzio is a member of the lab of Assistant Professor Jyoti Katoch and Assistant Research Professor Simranjeet Singh where he works on designing and understanding the properties of ultrathin materials, some of which are only one atom thick and known as two-dimensional materials.

“Ultimately, we want to probe and understand the electronics of these 2D materials,” Muzzio said. “This line of research has the potential to revolutionize how we live our lives.”

To create and test these materials, Muzzio relies on advanced equipment at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California and collaboration with scientists from around the world. During the school year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, he had been preparing to measure samples on the national laboratory’s sensitive spectrometer and attend training sessions at the facility. Those canceled visits to the national laboratory were set to be useful for more than just learning how to operate the spectrometer, Muzzio noted.

“The researchers who travel to or are permanently located at this facility are amongst the very best in their fields,” Muzzio said. “Learning from them is integral to my research and career advancement.”

After two months spent at home doing data analysis, Muzzio’s lab was approved to be one of the first to return to campus to conduct research. However, the process was far from normal.

“For two months since June, I was the only student working in my lab where, in the past, there were three graduate students and four regular undergraduate students,” Muzzio said. This meant he was forced to take on additional duties to maintain the research group’s equipment and even run his lab mates’ experiments for them.

“I feel like it’s rare you get such an opportunity to have an effect on your government.”

While acknowledging the difficulties this year has presented for him and his research, Muzzio wanted to keep the focus of his testimony on the struggles of his fellow graduate students at Carnegie Mellon and across the country.

“Graduate students are more than just researchers — we are a linchpin in the entire higher education system. We conduct groundbreaking research, drive day-to-day operations of our labs and teach and mentor undergraduate students,” Muzzio noted in his testimony. He went on to recount many stories from his peers who had dealt with challenges to their careers and lives brought on by COVID-19, from struggling with childcare to worrying about finishing their dissertations in time.

“What I was anxious about was misrepresenting, not representing or missing out on something crucial that the graduate student body feels in America,” Muzzio said, and that pressure drove him to wake up early and stay up late many days reaching out to students and writing his testimony.

Muzzio said he is grateful to have had supportive advisors and lab mates, and that the single biggest thing that universities, advisors and professors can do to help his peers is offer understanding.

“The product is going to be a function of the people who are providing that,” Muzzio said. “My research is going to be a product of how I feel from day-to-day.”

Since his testimony, Muzzio said many other graduate students have reached out to him with advice and thanks, and he feels lucky to have been able to represent his peers, university and community in such a prominent way.

“I feel like it’s rare you get such an opportunity to have an effect on your government,” he said.

■ Ben Panko

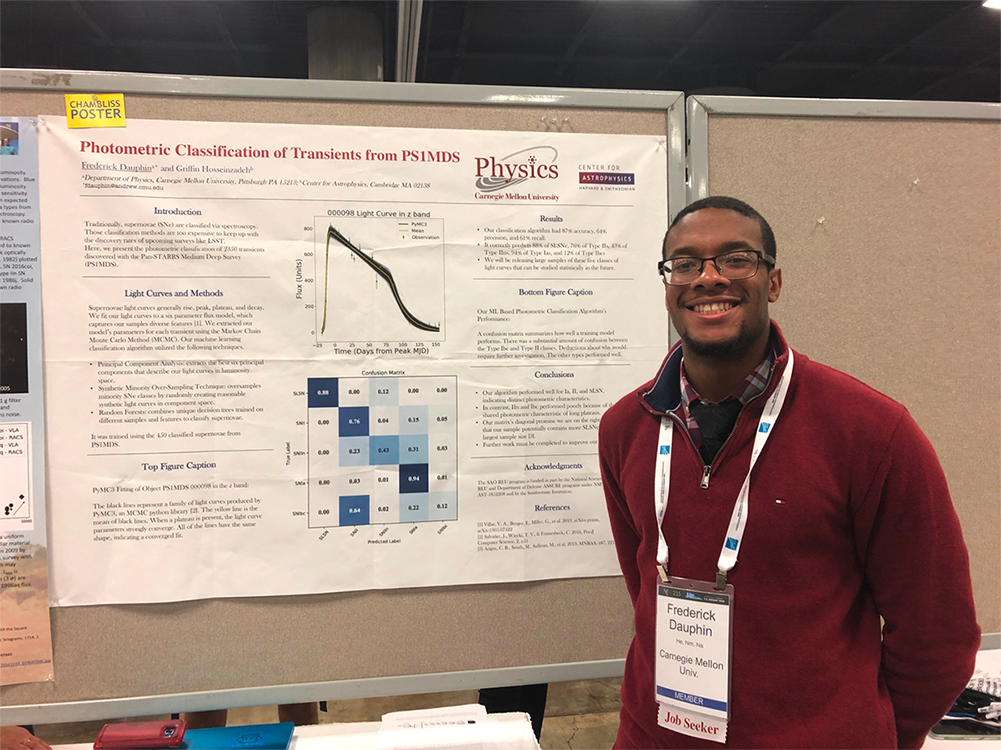

Shooting for the Stars

Dauphin, who graduated with his bachelor’s of science in physics, has a gravitational pull towards the mysteries of astrophysics. He’s fascinated by understanding the complexities of space through purely observational methods. There’s a satisfying challenge, he says, that comes from studying objects that push physics to its bounds, like neutron stars and black holes, without being able to touch or experiment on them.

Dauphin weaved this passion for discovering the unknown throughout his undergraduate years. He conducted research on protostars in molecular clouds during a Research Experience for Undergraduates at the University of Rochester and interned at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, where his work helping to develop new classification methods for supernovae was submitted to the American Astronomical Society journals for publication.

Within the Department of Physics, Dauphin pushed himself out of his comfort zone, taking courses in quantum physics and conducting research in biological physics. This breadth of study helped him foster his curiosity and develop what he calls physical intuition.

“The physics program teaches you how to think differently and work more efficiently,” said Dauphin. Many of his professors pushed their pupils to explain how something works using concepts purely from physics. “A lot of our homework problems are mathematical, but the more interesting problems asked us ‘why should something work this way?’ or ‘why does this make sense?’,” Dauphin explained. “It teaches you to think like a physicist and use all the tools you’ve learned over the years to tackle the problem.”

Now as a science support analyst at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), Dauphin has carried this intuition with him into his professional career. STScI is the science operations center for NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope. Dauphin is part of the Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) team, working to update one of their data processing pipelines. WFC3, a fourth-generation imager for Hubble, is its most technologically advanced camera, capable of capturing large-view, high-resolution images over a wavelength range of 200 to 1,700 nanometers. The long-term goal of Dauphin’s project is to help give the camera its own intuition by applying machine learning methods to the camera’s functionality.

For Dauphin, it wasn’t just physics that shaped his personal and professional growth.

Outside of academics, Dauphin devoted himself to the CMU community as a leader, peer, athlete and role model. He was a record-breaking jumper and captain on the track and field team; a brother and president of Sigma Alpha Epsilon (SAE); an orientation counselor and leader; and a representative for Plaidvocates, CMU’s student-athlete peer advocacy program.

“Those organizations are what made CMU home for me on top of the academics,” said Dauphin. And they helped him become the person he is today.

One of his favorite memories was organizing SAE’s Donut Dash, a foodie- and family-friendly race that raised over $80,000 for the Mario Lemieux Foundation’s Austin’s Playrooms Initiative in 2019.

His efforts as a leader and philanthropist earned Dauphin national recognition — he was awarded an Undergraduate Award of Distinction from the North American Interfraternity Council.“It’s one of the highest honors you can receive,” said Sam Waltemeyer, assistant director of Student Leadership, Involvement and Civic Engagement and Greek housefellow, who nominated Dauphin. Annually, the award recognizes eight to 10 young men from across all fraternities nationwide who embody the ideals of scholarship, leadership and service to others.

“I have come to know Fred as a humble, down-to-earth leader in the lab, on the track field and within the chapter, making him an ideal nominee for this distinguished award,” said Waltemeyer.

Dauphin’s time as a Plaidvocate also left a large mark on his life.

Plaidvocates lead by example. They serve as advocates, mentors and confidantes for all student-athletes. One of the most important duties is to foster a culture of healthy behaviors among students. Throughout the year, Plaidvocates lead educational, constructive conversations on stress and time management, nutrition, alcohol, drug use, harassment and sexual assault.

“Plaidvocates taught me what it means to be a dependable and accountable teammate and how to be there for someone when they need help,” Dauphin said.

“The physics program teaches you how to think differently and work more efficiently.”

Earlier this summer, Dauphin served as a panelist on the Mellon College of Science’s first virtual dialogue in a series on anti-racism, diversity, equity and inclusion (ADEI). The dialogue began as a starting point for understanding where MCS needs to improve its own efforts in addressing ADEI.

“I was excited to talk about my experience, what it’s like being a Black student at CMU, and to figure out how people could get more engaged with these issues,” Dauphin said.

He has also joined MCS’s ADEI committee. Made up of alumni, faculty, staff and students, the committee has been advising MCS Glen de Vries Dean Rebecca Doerge on how the college can improve its ADEI efforts and make the college a better, more welcoming place to learn and work.

The experience has been meaningful for the young graduate. He sees himself as the bridge between different generations. “As a fresh grad, I have a better understanding of what current students feel/need and can represent the new generation well,” Dauphin said.

■ Emily Payne